When Injustice, a Book, and a Cause Came Together

Grant Ujifusa, resident of The Hill at Whitemarsh

Long before becoming a resident at The Hill, Grant Ujifusa was a boy growing up on a sugar beet farm in northern Wyoming. It was there he had heard stories from his grandfather about the 110,000 Japanese Americans who had been rounded up and sent to internment camps. One of those camps was a mere 70 miles from his grandparents’ farm, which the family had owned since coming to America from Japan in 1907. A thousand miles from the West Coast, Grant’s family was not among those interned, but the stories his grandfather told made a long-lasting impression on him.

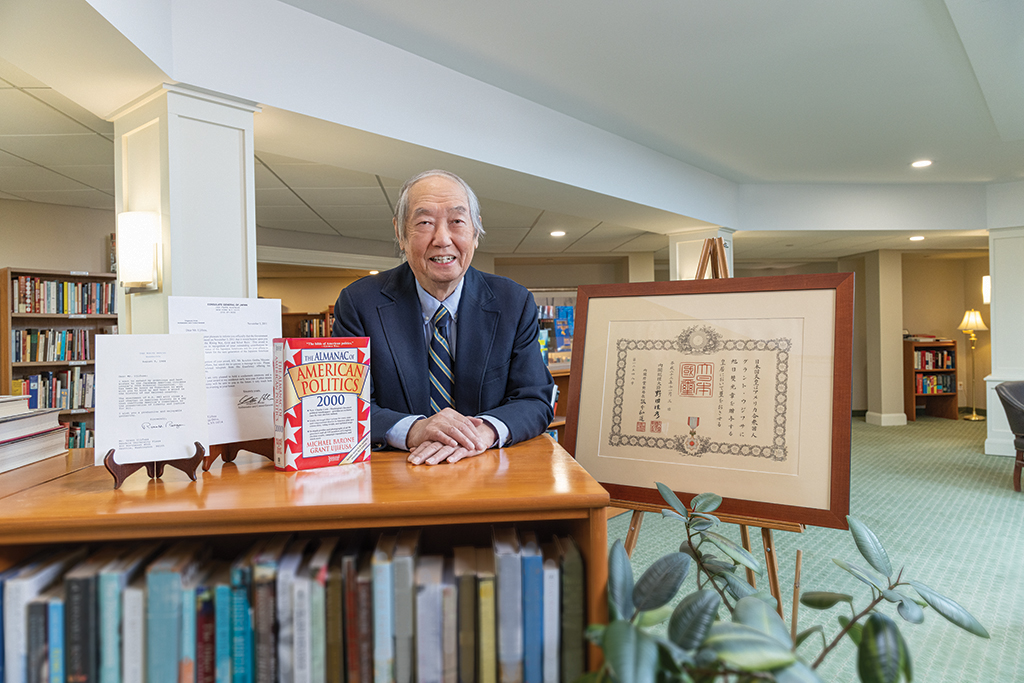

After graduating from Harvard, Grant kept those stories in the back of his mind as he pursued a career as a book editor at Random House while also writing a book of his own called “The Almanac of American Politics” with a friend from the student newspaper, the “Harvard Crimson.”

First published in 1972, “The Almanac” was a National Book Award finalist in 1973 and became a Washington bestseller in the years since.

Why?

“Because using words and numbers, the book laid out everything that was politically important in all the 535 congressional districts and the 50 states,” Grant said. “In short, the book covered the constituencies of all 535 Representatives and all 100 Senators. And constituencies determine how a politician votes.”

Both Tim Russert and George Will called “The Almanac” the “bible of American politics” because everyone on Capitol Hill and at the White House, along with the lobbyists, pollsters, and journalists–all the decision-makers in Washington–used the book, often many times a day.

Because of the book’s standing in Washington, Grant was approached by a group of Japanese elders who asked him to help them lobby the Japanese American Redress and Reparations bill, known as H.R. 442. The legislation was named to honor the unit of Japanese American combat soldiers who volunteered out of the camps to fight in the U.S. Army with huge distinction in Italy and France. The 442 won more Congressional Medals of Honor for its size and length of service than any other in U.S. Army military history.

“When I was asked, I was working as an editor at Random House, and I thought what they were trying to do was impossible,” said Grant. “But I was so touched by their passion that I agreed to become the Legislative Strategy Chair of the Japanese American Citizens League, our version of the NAACP.”

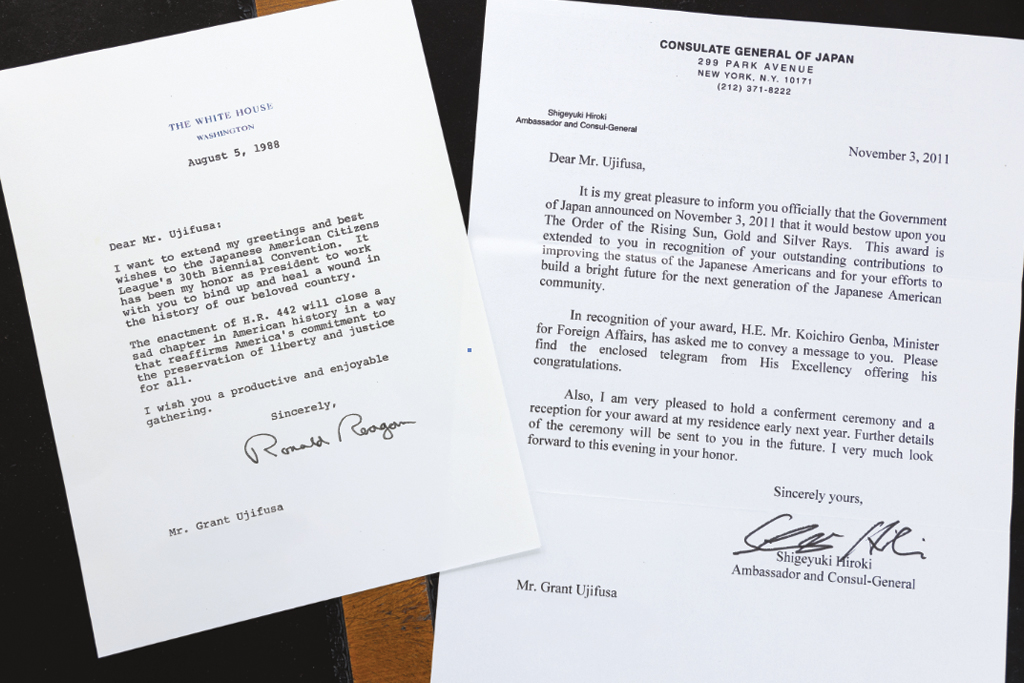

Thanks to the hard work of thousands of people and the commitment of U.S. Representative Barney Frank and Senator Spark Matsunaga, the H.R. 442 bill had cleared the House of Representatives and was sent to the Senate with a filibuster-proof majority.

As luck would have it, Grant was then editing a book for New Jersey Governor Tom Kean, who as a Republican governor had direct access to the President via something called “The Pouch.”

“Tom gave me a way to reach Reagan, whose Administration had for two years taken a public position against our bill,” Grant said. “To change Reagan’s mind, I had the sister of Kazuo Masuda write a letter to the President about her brother, who was to posthumously receive the Distinguished Service Cross after he was killed in action in Italy. But Kazuo was denied burial in his hometown cemetery in California by local authorities because he was a Japanese American.”

When his burial was denied, a then-26-year-old movie star named Army Captain Ronald Reagan came to speak at an event designed to get the authorities to change their minds, and the young Reagan was successful. He had famously said, “The blood that has soaked into the sand is all one color.”

When Reagan was reminded of the Masuda story and how he had spoken at the event, he changed his mind and decided to sign H.R. 442.

And so Grant became an essential force in getting Congress and the President to acknowledge, apologize, and provide monetary reparations for sending Japanese Americans to internment camps during the Second World War.

“I was the first to get a call from the White House once President Reagan had made the decision to sign the redress bill.”

– Grant Ujifusa

“Apart from moments I’ve had with family, Reagan’s decision to sign H.R. 442 was the happiest moment of my life.”

Because Grant achieved what once seemed impossible, the Japanese government awarded him the The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays, in 2012, which is the equivalent of a knighthood.

“It was a considerable honor,” Grant said about receiving the award. “It tells me that while there is always going to be darkness happening around us, we can make choices to be on the right side of history as we work to make sure that the good guys win in the end.”